Most people think back pain is just a muscle strain. But if your pain stays for weeks, gets worse when you stand, and shoots down your leg, it might be something deeper - spondylolisthesis. It’s not rare. About 6 in every 100 adults have it, and many don’t even know until they get an X-ray for something else. The spine slips - not dramatically, but enough to pinch nerves, tighten hamstrings, and make walking feel like a chore. And when conservative treatments fail, the big question becomes: should you fuse it?

What Exactly Is Spondylolisthesis?

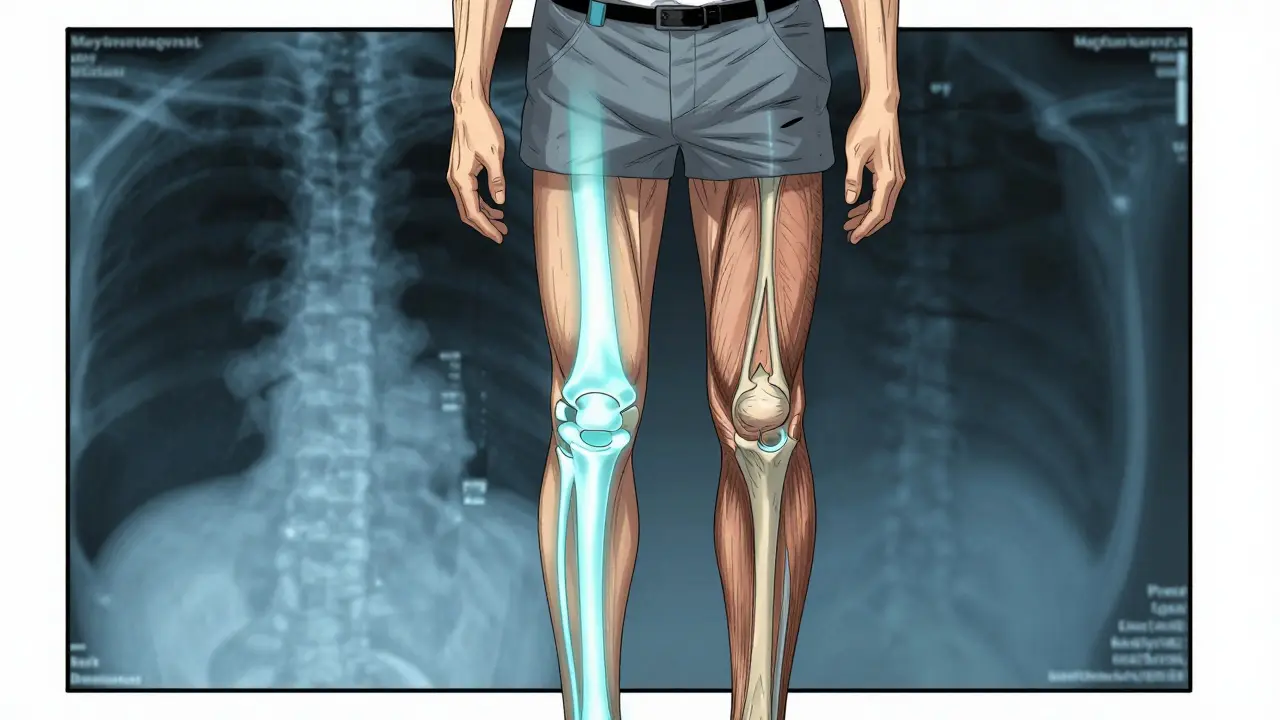

Spondylolisthesis comes from Greek: "spondylo" means vertebra, and "olisthesis" means slip. So, it’s when one bone in your lower spine slides forward over the one below it. Most often, it happens between L5 and S1 - the bottom of your lumbar spine and the top of your sacrum. This isn’t just a minor misalignment. When the slip passes 50% of the vertebral width (Meyerding Grade III or higher), it starts pressing on nerves, causing numbness, tingling, or weakness in the legs. There are five types, but only two matter for most adults. Degenerative spondylolisthesis makes up 65% of cases in people over 50. It’s not from trauma or genetics - it’s from years of wear and tear. Arthritis breaks down the discs and joints that hold vertebrae in place. The spine slowly gives way. The other common type is isthmic spondylolisthesis, which starts with a tiny stress fracture in the pars interarticularis - a thin bone bridge connecting the upper and lower joints of a vertebra. This often begins in childhood during sports like gymnastics or football, but doesn’t cause pain until middle age.Why Does It Hurt?

Pain isn’t always from the slip itself. It’s from what happens around it. When L5 slides forward, the disc above it gets squished. That disc degenerates. The facet joints, which normally glide smoothly, grind together. Muscles around the spine tighten up trying to stabilize it. That’s why 70% of people with this condition have tight hamstrings - your body’s way of locking the pelvis to reduce movement. The pain is usually dull and deep in the lower back. It flares up when you stand or walk, especially for long periods. Sitting or bending forward often brings relief because it opens up the space around the nerves. About half of people with spondylolisthesis feel no pain at all. But for those who do, symptoms can creep up slowly. You might notice you can’t walk as far as you used to. Or your back feels stiff in the morning. Then comes the sciatica - a sharp, electric pain running down one or both legs.How Is It Diagnosed?

You won’t find this with a physical exam alone. The gold standard is a standing lateral X-ray. It shows exactly how far the vertebra has slipped. Doctors grade it from I to IV using the Meyerding scale: Grade I is less than 25% slippage, Grade IV is more than 75%. Most cases are Grade I or II - manageable without surgery. But X-rays don’t show nerves. That’s where MRI comes in. It reveals if the slipped bone is pinching the spinal cord or nerve roots. CT scans give a clear picture of the bone structure - especially useful if there’s a suspected fracture in the pars. A 2023 study found that the severity of disc degeneration matched up more closely with age and symptom duration than with the grade of slippage. That means two people with the same slip percentage can have wildly different pain levels. Treatment should focus on symptoms, not just the X-ray.Conservative Treatment: What Actually Works?

For most people, surgery isn’t the first step. In fact, 80% of cases improve with non-surgical care. The key is consistency. Physical therapy is the backbone. Not just stretching - though hamstring flexibility matters - but core strengthening. Exercises that target the transverse abdominis and multifidus muscles help stabilize the spine. A good program lasts 12 to 16 weeks. Only about 65% of people stick with it long enough to see results. If you skip sessions, you’re wasting time. NSAIDs like ibuprofen help with inflammation and pain, but they don’t fix the root problem. Epidural steroid injections can give temporary relief - often lasting 3 to 6 months - by reducing swelling around compressed nerves. They’re not a cure, but they can buy time to heal or prepare for surgery. Activity modification is crucial. Avoid sports that hyperextend the spine: gymnastics, football, weightlifting. Even heavy lifting at the gym can make things worse. Walking is fine. Swimming, especially backstroke, is excellent. Cycling on a recumbent bike keeps the spine in a flexed position, which reduces pressure.

When Is Surgery Considered?

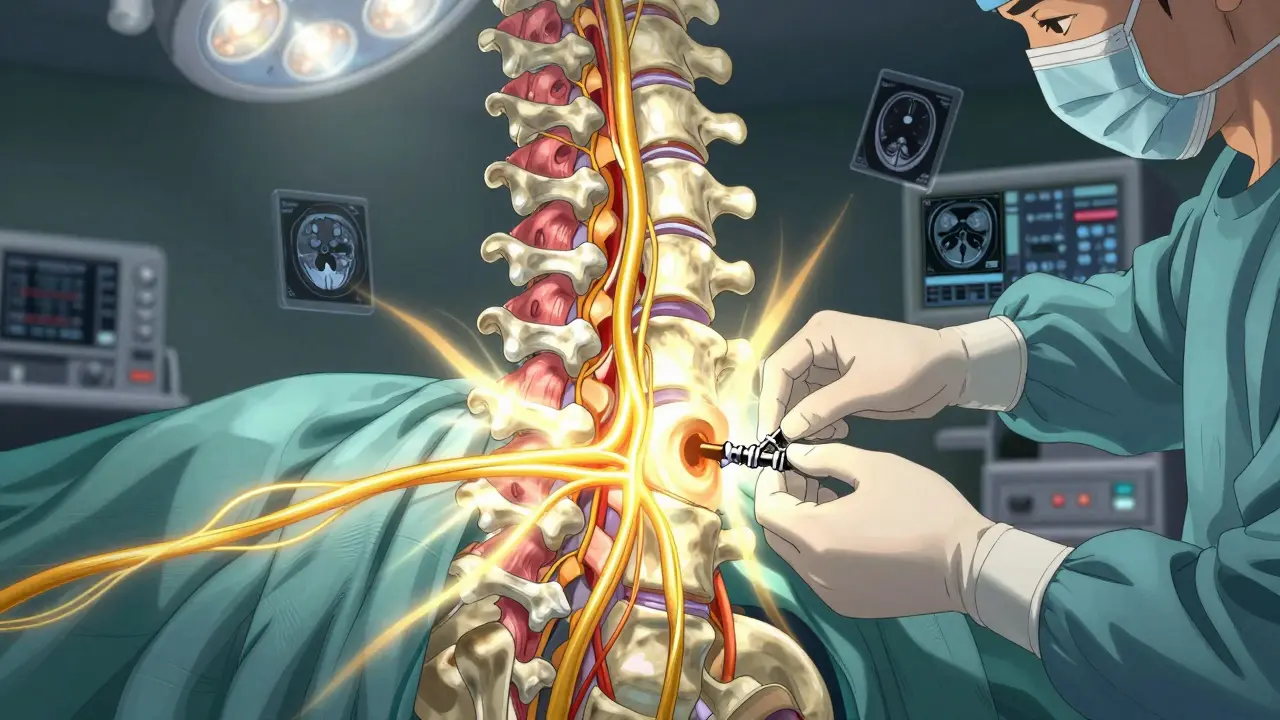

Surgery isn’t for everyone. It’s for people who’ve tried 6 to 12 months of physical therapy, pain management, and lifestyle changes - and still can’t walk without pain, can’t sleep, or are losing muscle strength in their legs. The main goal of surgery is to stop the slip from getting worse and to relieve pressure on nerves. That’s done through spinal fusion - permanently joining two vertebrae together so they heal into one solid bone. It’s not a quick fix. Recovery takes a year or more. But for the right person, it changes everything.Fusion Options: What’s the Best Choice?

There are three main fusion techniques, each with pros and cons. Posterolateral fusion (PLF) is the oldest method. Surgeons place bone grafts along the back of the spine and secure it with screws and rods. It’s used in about 55% of cases. Success rates are good for Grade I-II slips - 75-85%. But for Grade III-IV, it drops to 60-70%. Why? Because it doesn’t restore disc height or open up the nerve pathways. The slip stays, and nerves stay pinched. Interbody fusion - including PLIF (posterior lumbar interbody fusion) and TLIF (transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion) - is now the preferred choice for moderate to severe cases. Here, the surgeon removes the damaged disc and inserts a spacer filled with bone graft between the vertebrae. This lifts the spine back into alignment, opens the nerve tunnels, and gives the bone a better surface to fuse. Success rates? 85-92% across all grades. It’s more complex, but the results are better. Minimally invasive fusion (MIS) is growing fast. Instead of a large incision, surgeons use small tubes and cameras. Recovery is faster - hospital stays drop from 3-5 days to 1-2. But it’s not for everyone. If the slip is severe or there’s major instability, MIS might not provide enough correction. Still, for Grade I-II cases, it’s a strong option with less tissue damage and lower infection risk.What About Newer Options?

In 2022, the FDA approved two new interbody devices designed specifically for spondylolisthesis. Early data shows 89% fusion rates at six months - better than older implants. Some surgeons are also using bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) or stem cells to boost healing. A 2023 trial found BMP-2 raised fusion success to 94% in high-risk patients - smokers, diabetics, or those with severe degeneration. But fusion isn’t the only path. Dynamic stabilization devices - flexible rods that limit movement without fully fusing the spine - are being tested. They work best for mild cases. Success rates hover around 76% after five years. That’s lower than fusion’s 88%, but they preserve motion. Long-term data is still limited.

Doreen Pachificus

January 3, 2026 AT 12:38Been dealing with this for years. My doc said Grade II, and I just kept walking and doing yoga. No surgery. Still can’t run, but I can garden now. Funny how the body adapts if you stop fighting it.

Ethan Purser

January 5, 2026 AT 07:06THIS. This is the exact moment your spine says ‘I’ve had enough.’ I used to think pain was weakness leaving the body. Turns out, it’s your L5 screaming for mercy. 🤯

Cassie Tynan

January 6, 2026 AT 18:28So let me get this straight - we’re spending $50k to weld two bones together so you can stop feeling like a broken hinge? And the real cure is… sitting down? 🤔 I mean, if your spine’s a toaster, why not just unplug it?

Rory Corrigan

January 8, 2026 AT 08:24life is pain. 🥲 spine is just the latest messenger. fusion ain't the answer - it's the middle finger to gravity. but hey, at least you get a new spine tattoo.

Stephen Craig

January 9, 2026 AT 00:34Conservative treatment works if you do it right. Most people quit at week 4. That’s the problem.

Roshan Aryal

January 10, 2026 AT 15:30Western medicine again - cut, weld, drug. In India, we use yoga, turmeric, and silence. No screws. No scars. Just breath. You Americans turn every ache into a surgery waiting to happen.

Jack Wernet

January 11, 2026 AT 18:35It is imperative to underscore that spinal fusion, while efficacious in select clinical populations, must be predicated upon a comprehensive multidisciplinary evaluation, including psychosocial determinants of pain perception and functional capacity. The data presented herein is methodologically robust.

en Max

January 12, 2026 AT 05:35It is critical to recognize that the biomechanical implications of spinal fusion - particularly in the context of adjacent segment disease (ASD) - necessitate a longitudinal, evidence-based approach to patient selection, with particular attention to preoperative sagittal alignment, bone mineral density, and neuromuscular compensation patterns. Failure to address these variables correlates strongly with suboptimal outcomes.

Angie Rehe

January 13, 2026 AT 12:44Why are you all still talking about PT? I had a Grade III slip and my surgeon said ‘you’re not walking again without fusion’ - and he was right. I waited six months because I was scared. Now I can’t even lift my kid. You people are risking your lives for ‘natural healing.’

Enrique González

January 13, 2026 AT 20:19I didn’t believe in surgery until I couldn’t tie my shoes. Now I walk 3 miles a day. It’s not perfect - but it’s mine. Don’t let fear make the call. Let your body tell you when it’s done.

Connor Hale

January 14, 2026 AT 00:57It’s weird how the same X-ray that looks terrifying to one person is just a footnote to another. The body doesn’t care about grades - it cares about movement. If you’re not in pain, why fix what isn’t broken?

Vicki Yuan

January 14, 2026 AT 15:19For those considering fusion: ensure your surgeon has performed at least 50 TLIF procedures in the past year. Verify the implant’s fusion rate in peer-reviewed literature. Document your baseline functional status using the Oswestry Disability Index. And please - stop Googling ‘spinal fusion horror stories’ at 2 a.m.