What Is Retinal Vein Occlusion?

Retinal vein occlusion (RVO) happens when a vein in the retina gets blocked, stopping blood from flowing out. The retina is the light-sensitive layer at the back of your eye that turns images into signals your brain understands. When blood backs up because of a blockage, fluid leaks into the retina, causing swelling - especially in the macula, the part responsible for sharp central vision. This leads to sudden, painless vision loss, often in just one eye.

There are two main types: central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO), which blocks the main vein, and branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO), which affects smaller branches. CRVO tends to cause more severe vision loss, while BRVO often affects only a portion of your vision, like the top or bottom half. Both can lead to permanent damage if not treated quickly.

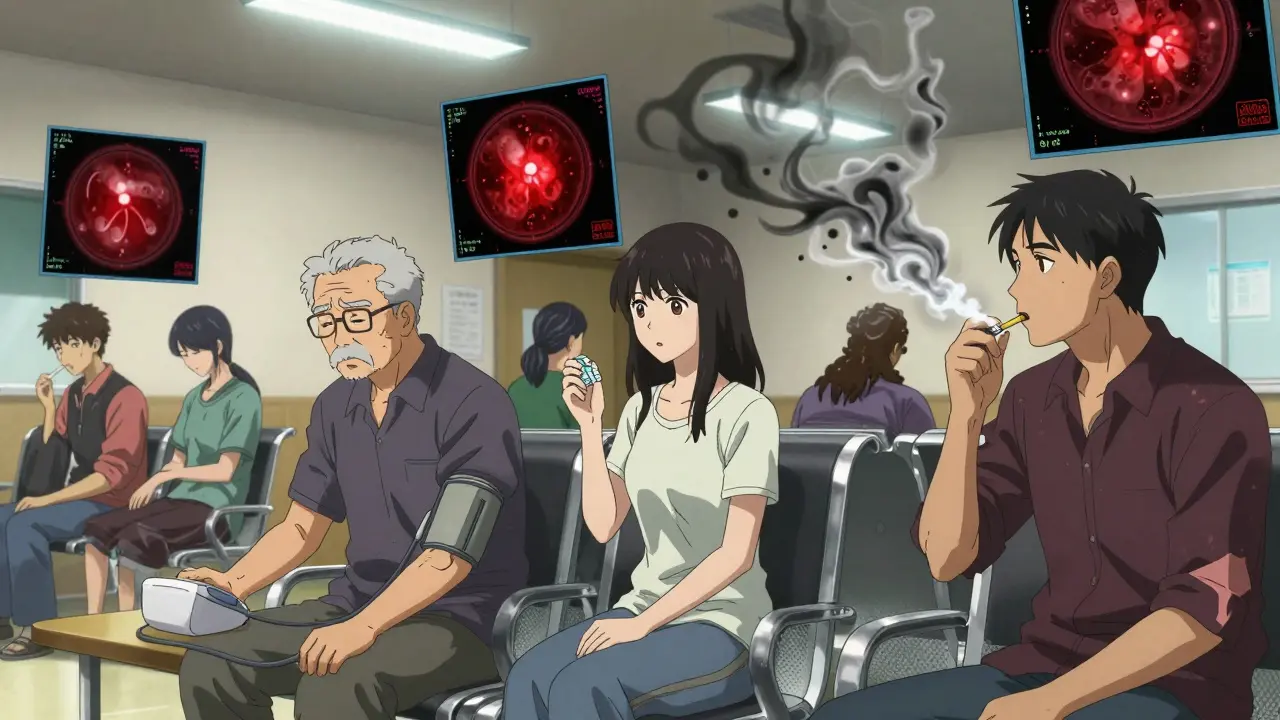

Who’s Most at Risk?

Age is the biggest factor. Over 90% of CRVO cases happen in people over 55, and more than half of all RVO cases occur in those over 65. But it’s not just an older person’s disease - about 5 to 10% of cases affect people under 45, especially women on birth control pills.

High blood pressure is the most common underlying issue. Up to 73% of CRVO patients over 50 have uncontrolled hypertension. Even in younger patients, high blood pressure shows up in about 25% of cases. Diabetes is another major player - around 10% of RVO patients over 50 have it, and it makes recovery harder. High cholesterol, especially levels above 6.5 mmol/L, is present in 35% of cases regardless of age.

Glaucoma also increases risk, particularly when the blockage happens near the optic nerve. Smoking raises your chances by 25-30%, and being overweight or inactive adds to the problem. These factors all contribute to hardening and narrowing of the arteries, which can press on veins and cause blockages.

In younger patients, blood disorders like polycythemia vera, multiple myeloma, or inherited clotting conditions like factor V Leiden are more likely causes. If you’re under 45 and get RVO, doctors will often check for these hidden issues.

Why Injections Are the Standard Treatment

There’s no way to unblock the vein once it’s clogged. So treatment doesn’t fix the blockage - it tackles the damage it causes: macular edema, or fluid buildup in the center of the retina. That’s where injections come in.

The two main types are anti-VEGF injections and corticosteroid implants. Anti-VEGF drugs - like ranibizumab (Lucentis), aflibercept (Eylea), and bevacizumab (Avastin) - block a protein called vascular endothelial growth factor that causes leaking blood vessels. Corticosteroid implants, like Ozurdex (dexamethasone), reduce inflammation and swelling.

Studies show anti-VEGF injections work well. In the BRAVO trial, patients using ranibizumab gained an average of 16.6 letters on an eye chart after a year. In the COPERNICUS trial, aflibercept improved vision by 18.3 letters. That’s the difference between barely reading a menu and reading street signs again.

For patients who don’t respond well to anti-VEGF, Ozurdex can help. The GENEVA study found that nearly 28% of CRVO patients gained 15 or more letters of vision after six months with the implant, compared to just 13% without it.

How Often Do You Need Injections?

It’s not a one-time fix. Most patients start with monthly injections until the swelling goes down. Then, doctors switch to an "as-needed" schedule, checking the eye every 4 to 8 weeks with an OCT scan. This scan measures fluid thickness in the retina - treatment usually starts when it’s over 300 micrometers and stops when it drops below 250.

Real-world data shows people need about 8 to 12 injections in the first year. Some patients respond faster, others need more. A newer approach called "treat-and-extend" is becoming popular - you start monthly, then gradually stretch the time between shots if the eye stays stable. One 2023 study showed this cuts injection frequency by 30% without losing results.

Bevacizumab (Avastin) is often used off-label because it’s much cheaper - around $50 per dose compared to $2,000 for Lucentis or Eylea. In public hospitals, it’s used in 60-70% of cases. Private clinics use it less, but many patients opt for it to save money.

What to Expect During the Procedure

The injection takes less than 10 minutes. Your eye is numbed with drops, cleaned with antiseptic, and held open with a tiny clamp. The doctor uses a very fine needle to inject the medicine into the white part of your eye, just behind the iris. You might feel pressure, but not pain.

Afterward, you might notice redness, floaters, or a small spot of blood on the white of your eye - these are normal and clear up in a few days. About 25-30% of patients get a subconjunctival hemorrhage. A temporary spike in eye pressure happens in 15-20% of cases, but it’s usually managed with drops.

Serious complications are rare. Endophthalmitis - a severe eye infection - occurs in only 0.02-0.1% of injections. Still, if you get sudden pain, worsening vision, or light sensitivity after an injection, call your doctor right away.

Side Effects and Long-Term Concerns

Anti-VEGF injections are generally safe over time, but they require frequent visits. Many patients say the anxiety before each injection is worse than the shot itself. Some develop "treatment fatigue" and miss appointments, even when their vision is improving.

Steroid implants like Ozurdex can cause cataracts in 60-70% of patients who still have their natural lens. They also raise eye pressure in about 30% of cases, sometimes requiring medication or surgery. That’s why most doctors try anti-VEGF first, especially for younger patients.

Financial burden is real. Even with insurance, out-of-pocket costs for Lucentis or Eylea can hit $150-$250 per injection. Ozurdex can cost over $2,500 per implant. Some patients choose Avastin for affordability, even if it’s not officially approved for RVO.

What’s Next in Treatment?

The future of RVO treatment is moving away from monthly shots. A new delivery system called Susvimo, approved for macular degeneration, is now being tested for RVO. It’s a tiny implant that releases ranibizumab slowly for months, reducing injections from monthly to quarterly.

Gene therapy is also in the works. RGX-314, currently in Phase II trials, aims to make your eye produce its own anti-VEGF protein after a single injection. If it works, it could change everything.

Another promising option is OPT-302, a new drug that blocks a different growth factor (VEGF-C/D) and is being tested alongside aflibercept for patients who don’t respond to standard treatment.

Doctors are also using new imaging tools like OCT angiography to predict who will respond best to which treatment - meaning care is becoming more personalized.

What You Can Do Now

If you’ve been diagnosed with RVO, follow your doctor’s plan. Don’t skip appointments. Even if your vision improves, the risk of recurrence stays high. Control your blood pressure, manage diabetes if you have it, quit smoking, and get your cholesterol checked.

If you’re under 45 and had RVO, ask about blood tests for clotting disorders. If you’re on birth control, talk to your doctor about alternatives.

And if you’re struggling with the cost or the emotional toll of frequent injections, speak up. Many clinics have financial aid programs. Support groups like the American Macular Degeneration Foundation connect patients who’ve been through it - hearing their stories helps.

Can Vision Be Fully Restored?

It depends. About 30-40% of patients treated early reach 20/40 vision or better - enough to drive and read normally. Others see partial improvement. A small group won’t regain much vision, especially if treatment was delayed.

Early treatment is everything. If you notice sudden blurring or vision loss in one eye, don’t wait. See an eye doctor within 24 hours. The sooner you start injections, the better your chances of saving your sight.

Can retinal vein occlusion be cured?

No, RVO cannot be cured - the blocked vein doesn’t reopen. But treatment can stop further damage and often restore lost vision by reducing swelling. Most patients stabilize or improve with injections, especially when treatment starts early.

Are eye injections painful?

Most patients feel only slight pressure or a brief sting. The eye is numbed with drops, and the procedure takes less than 10 minutes. The anxiety before the shot is usually worse than the actual experience.

How many injections will I need?

Most people need 8-12 injections in the first year. After that, the frequency drops to as-needed, based on OCT scans showing fluid levels. Treat-and-extend protocols can reduce the total number by up to 30%.

Is Avastin safe for retinal vein occlusion?

Yes. Although Avastin is not FDA-approved for eye use, it’s widely used off-label for RVO and has been shown in studies to be as effective as more expensive drugs like Lucentis and Eylea. It’s much cheaper and commonly used in public hospitals and by patients needing cost-effective care.

Can I drive after an eye injection?

You shouldn’t drive immediately after. Your vision may be blurry for a few hours due to the dilating drops and the injection itself. Arrange for someone to drive you home. Most people can resume normal activities the next day.

Will I need injections for the rest of my life?

Not necessarily. Many patients reach a point where they only need injections every few months or even less often. Some stop entirely after a few years if the eye stays stable. But RVO is a chronic condition, so regular monitoring is needed for life to catch any recurrence early.

srishti Jain

December 30, 2025 AT 22:19Cheyenne Sims

January 1, 2026 AT 15:01Shae Chapman

January 3, 2026 AT 07:11Nadia Spira

January 3, 2026 AT 13:46henry mateo

January 3, 2026 AT 19:06Kunal Karakoti

January 4, 2026 AT 05:19Kelly Gerrard

January 5, 2026 AT 18:07Glendon Cone

January 6, 2026 AT 22:03Henry Ward

January 7, 2026 AT 10:18