For many people, opioids are a last-resort tool for managing severe pain. But for others, they become a trap. The line between relief and dependence isn’t always clear-and getting it wrong can cost lives.

When Opioids Are Actually Needed

Opioids aren’t meant for everyday aches. They’re not the first thing you reach for when your back hurts or your knee flares up. The CDC’s 2022 guidelines make this clear: non-opioid treatments like physical therapy, NSAIDs, or even cognitive behavioral therapy should come first. Opioids are reserved for cases where pain is severe, sudden, and expected to be short-lived-like after major surgery, a broken bone, or serious trauma. Even then, the goal isn’t to keep you on them long. A typical prescription for acute pain should last no more than a few days. Studies show most people don’t need more than three to seven days of opioids after surgery. Yet, in 2020, nearly half of all opioid prescriptions for acute pain were for more than 10 days. That’s not just unnecessary-it’s risky. For chronic pain-pain lasting longer than three months-the threshold is even higher. Opioids are only considered if every other option has failed. That means trying exercise, acupuncture, nerve blocks, antidepressants, or anticonvulsants first. If none of those help enough, and your pain is still disabling, then opioids might be tried as a short-term experiment. But even then, doctors should be watching closely.How Much Is Too Much?

Dose matters. A lot. The risk of overdose doesn’t creep up slowly-it jumps. For every extra 10 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) you take per day between 20 and 50 MME, your chance of overdose goes up by 8%. Between 50 and 100 MME, it jumps to 11% per 10 MME. That’s not a small increase. It’s a warning sign. Most guidelines agree: 50 MME per day is the upper limit for most patients. Anything above that requires strong justification. At 90 MME or higher, the risk of addiction and overdose rises sharply. The VA/DoD guidelines say that patients on doses over 100 MME per day have a 26% chance of developing opioid use disorder. That’s more than one in four. And it’s not just about the number on the bottle. Mixing opioids with other depressants-like benzodiazepines for anxiety or sleep-multiplies the danger. The CDC found that people taking both have 3.8 times the risk of overdose compared to those on opioids alone. In some cases, that risk jumps to over 10 times higher.Who’s Most at Risk?

Not everyone who takes opioids ends up dependent. But some people are far more vulnerable. History matters. If you’ve struggled with substance use before-even alcohol or nicotine-your risk of opioid use disorder doubles or triples. Age plays a role too. People over 65 metabolize drugs slower, so even standard doses can build up and cause breathing problems. Genetics also play a part. Studies show 40 to 60% of vulnerability to addiction is inherited. That means if someone in your family has had a problem with drugs or alcohol, you might be at higher risk, even if you’ve never used opioids before. Other red flags include untreated depression, anxiety, or trauma. Pain and mental health are deeply linked. When both are untreated, opioids can become a crutch-not a cure. That’s why doctors are now trained to screen for mental health conditions before prescribing.

How Doctors Monitor You

If you’re on opioids long-term, your doctor shouldn’t just write a prescription and forget about you. Regular check-ins are required. The VA/DoD guidelines say stable patients should be seen at least every three months. High-risk patients-those on higher doses, with a history of addiction, or taking other sedatives-need monthly visits. What happens in those visits? It’s not just about asking, “Does the pain feel better?” Doctors use tools like the Pain Disability Index to measure how much pain is affecting your daily life. They check urine samples to make sure you’re taking what’s prescribed and nothing else. They use the Current Opioid Misuse Measure to spot warning signs: hoarding pills, running out early, doctor shopping, or using them for anything other than pain. If you’re not improving-if your pain hasn’t gone down, or your ability to work, walk, or sleep hasn’t gotten better-then continuing opioids doesn’t make sense. That’s when tapering starts.Tapering Off: Slow and Safe

Stopping opioids cold turkey is dangerous. It can trigger severe withdrawal: nausea, shaking, insomnia, anxiety, even seizures. Worse, it can push people back to street drugs like heroin or fentanyl because the pain returns and they’re desperate. Tapering isn’t one-size-fits-all. For someone who’s been on opioids for years with no side effects and some benefit, a slow taper-reducing by 2% to 5% every four to eight weeks-is safest. If you’re not improving, or you’re developing tolerance, a moderate taper of 5% to 10% every four to eight weeks is common. If you’re on over 90 MME per day or having serious side effects, a faster taper of 10% per week may be needed. The key is collaboration. You and your doctor should make this decision together. If you feel rushed or forced off opioids without a plan, that’s not care-that’s abandonment.

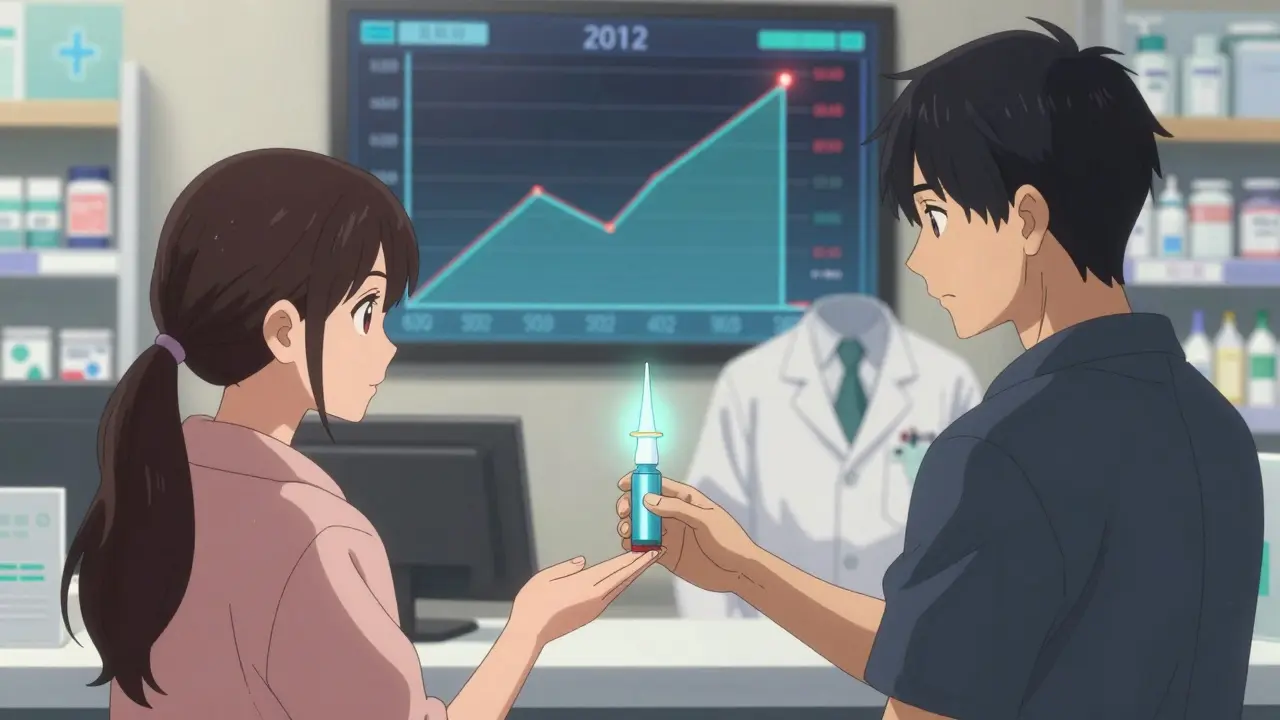

What’s Being Done to Fix This

The good news? Prescribing has dropped. In 2012, doctors wrote 81.3 opioid prescriptions for every 100 people in the U.S. By 2020, that number had fallen to 46.7. That’s a 42.5% drop. More doctors are checking prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs) before writing a script. Forty-nine states now have real-time PDMPs, and 87% of prescriptions are checked against them. Naloxone, the drug that reverses overdoses, is now available in 51% of U.S. hospitals as a standing order for at-risk patients. That’s up from 18% in 2016. More pharmacies offer it without a prescription. More first responders carry it. Research is moving fast too. The NIH’s HEAL Initiative has poured $1.5 billion into finding non-addictive pain treatments. As of late 2023, 37 new pain drugs-none opioids-are in late-stage clinical trials. Some target nerve pain differently. Others use the body’s own pain-blocking systems. These could change everything.What You Can Do

If you’re on opioids:- Ask: Is this still helping me function? Not just reduce pain, but let me sleep, move, work, or play with my kids?

- Ask: Am I taking more than I need? Keep track of how many pills you use each day. If you’re not using them all, talk to your doctor about reducing the dose.

- Ask: Do I have naloxone? If you’re on 50 MME or more, or take benzodiazepines, you should have it. Keep it at home. Teach someone how to use it.

- Ask: Have I tried everything else? If you haven’t done physical therapy, acupuncture, or counseling, ask if those could help before increasing your dose.

- Don’t ignore signs: hoarding pills, mood swings, secrecy, or missing prescriptions.

- Don’t shame. Offer support. Say: “I care about you. Let’s talk to your doctor.”

- Know where to turn. The SAMHSA National Helpline (1-800-662-HELP) is free, confidential, and available 24/7.

It’s Not About Fear-It’s About Balance

Opioids aren’t evil. They’ve helped people with cancer, end-of-life pain, and traumatic injuries live with dignity. But they’re powerful tools that demand respect. The goal isn’t to cut everyone off. It’s to make sure no one is left on them longer than needed, and no one is left without help when things go wrong. The science is clear: for most chronic pain, opioids don’t work well long-term-and the risks grow fast. But for the right person, at the right time, with the right support, they can still be part of the solution.Are opioids ever safe for long-term chronic pain?

Opioids can be used for chronic pain only after all other treatments have failed, and only if the benefits clearly outweigh the risks. Even then, they’re not a cure-they’re a temporary tool. Most patients don’t see lasting improvement after six months. Doctors should regularly reassess whether the dose is still needed, and tapering should be planned from the start.

Can I get addicted if I take opioids exactly as prescribed?

Yes. Physical dependence is different from addiction, but it can happen even with perfect use. Dependence means your body adapts to the drug, so stopping causes withdrawal. Addiction is compulsive use despite harm. About 8-12% of people on long-term opioids develop addiction. Risk goes up with higher doses, past substance use, or mental health conditions.

What should I do if I’m on opioids and want to stop?

Never quit cold turkey. Talk to your doctor about a tapering plan. A slow, personalized reduction-like cutting 2-5% every few weeks-is safest. If you’ve been on opioids for years, you may need help managing withdrawal symptoms or underlying pain. Support from a pain specialist or addiction counselor can make a big difference.

Is it true that most opioid overdoses happen from prescriptions?

No. While prescription opioids started the crisis, most overdose deaths now involve illicit drugs like fentanyl. But prescriptions still play a role. Many people who later use street drugs started with a legitimate prescription. Unused pills left in medicine cabinets are also a major source of diversion-especially for teens and young adults.

Why do some doctors refuse to prescribe opioids anymore?

Many doctors fear legal or regulatory consequences after past crackdowns. Some have been punished for overprescribing. Others don’t feel trained to manage opioid risks. But the CDC’s 2022 guidelines emphasize that doctors shouldn’t refuse opioids outright-they should use them wisely. The problem isn’t prescribing-it’s prescribing without monitoring, without alternatives, and without a plan to taper.

What are the alternatives to opioids for chronic pain?

There are many. Physical therapy, exercise, cognitive behavioral therapy, acupuncture, nerve blocks, and certain antidepressants or antiseizure drugs (like gabapentin or duloxetine) are often more effective long-term. New non-opioid drugs are in development, with 37 currently in late-stage trials. For many, combining these approaches works better than any single drug.

Lawver Stanton

January 1, 2026 AT 16:51Look, I get it - opioids are scary. But I’ve been on them for three years after a car crash that shattered my spine. I’m not high, I’m not stealing pills, I’m not chasing highs. I’m just trying to sit up without screaming. My doctor says I’m stable. So why does everyone act like I’m a junkie just because I need these to breathe? I don’t owe anyone an apology for not being dead.

And yeah, I know about the risks. I read the CDC guidelines. But none of those studies ever asked someone like me what it’s like to wake up every morning and know that if you skip a dose, your body turns into a war zone. You can’t just ‘try physical therapy’ when your vertebrae are held together by titanium and wishful thinking.

Stop preaching. Start listening.

And no, I won’t taper unless my pain gets better - not because some algorithm says so.

I’m not a statistic. I’m a person who still gets to see my kid graduate because I’m not in bed crying all day.

So yeah. I’m still on them. And I’m not sorry.

Also, naloxone? I’ve got two. I keep one in my truck. I’ve taught my sister how to use it. I’m not careless. I’m just surviving.

That’s it. I’m done talking to people who think pain is a moral failing.

Sara Stinnett

January 2, 2026 AT 03:27How quaint. We’ve turned medical necessity into a moral litmus test. The same people who would never question a diabetic’s insulin now treat opioid users like they’ve committed a felony just by existing. The irony is palatable - we’ve weaponized caution into cruelty.

Let me be clear: opioids are not the problem. The problem is the bureaucratic theater masquerading as care. Doctors who refuse to prescribe because they’re terrified of audits, not because they’re afraid of addiction. Patients who are abandoned mid-taper because ‘we don’t have time’ - as if human suffering is a scheduling conflict.

And let’s not forget the ‘non-opioid alternatives’ that are either ineffective, inaccessible, or priced like luxury vacations. Acupuncture? Great. If you live in a city with insurance that covers it. Physical therapy? Wonderful - if your job doesn’t require you to lift 50 pounds or stand on your feet for 12 hours.

We didn’t fix the system. We just made the pain invisible. And now we’re proud of ourselves for pretending it doesn’t exist.

What’s next? Denying cancer patients morphine because ‘maybe they’re just being dramatic’?

linda permata sari

January 2, 2026 AT 04:32As someone from Indonesia where pain management is still a luxury, I’ve seen people die because they couldn’t get even basic meds. Here in the U.S., we’re having a moral panic over pills while millions in the Global South beg for a single tablet.

It’s not about fear. It’s about privilege.

We have the resources, the science, the training - yet we’re arguing about whether someone deserves to sleep through the night. Meanwhile, my cousin in Jakarta is crushing aspirin into powder and mixing it with tea because the clinic ran out of anything stronger.

Can we fix this? Yes. But first, we have to stop treating pain like a debate topic and start treating it like a human right.

And no - I’m not saying everyone needs opioids. But I’m saying no one should be denied them because someone else got it wrong.

Empathy > bureaucracy.

Always.

❤️

Brandon Boyd

January 2, 2026 AT 13:25Hey - I’ve been there. I was on 80 MME for two years after a work injury. I thought I was fine until I realized I hadn’t played with my dog in months because I was too numb to care. Then I started tapering - slow, 5% every six weeks. It sucked. I cried. I hated my doctor. But I didn’t go back to pills.

And here’s the thing - I didn’t get better because I stopped opioids. I got better because I started moving again. Yoga. Walking. Therapy. I found a pain specialist who didn’t just hand me scripts - he helped me rebuild my life.

You don’t have to choose between pain and freedom. You just have to be willing to try something new.

It’s not easy. But it’s worth it.

And if you’re scared? Find someone who’s been through it. Talk to them. You’re not alone.

You got this. 💪

John Chapman

January 4, 2026 AT 02:42THIS. THIS RIGHT HERE. 🙌

I was on 120 MME for 5 years after a motorcycle crash. My doctor told me I’d be on them forever. I believed him.

Then I met a physical therapist who said, ‘You’re not broken - you’re just stuck.’

She didn’t give me pills. She gave me hope.

I’m off opioids now. I hike. I dance with my wife. I sleep through the night.

It wasn’t magic. It was work. And I needed someone who didn’t give up on me.

If you’re still on them? Don’t panic. Just ask: ‘What’s one small thing I can do today to feel more alive?’

Start there. I did. And I’m so glad I did. 🌱❤️

Urvi Patel

January 5, 2026 AT 14:59anggit marga

January 6, 2026 AT 05:12Stewart Smith

January 7, 2026 AT 21:58So… you’re saying if I’m on 40 MME and I’ve been stable for 4 years, I should just… stop? Because some algorithm says so?

What if I’m not improving? What if I’m just… not getting worse?

I’m not addicted. I’m not hoarding. I’m not mixing with benzos. I’m just… here.

And now you want me to risk withdrawal for… what? A chance I might feel 10% better?

Yeah. I’ll pass.

Also - my dog sleeps on my lap every night. I don’t think he’d understand why I suddenly can’t sit down anymore.

So no.

Not today.

Retha Dungga

January 8, 2026 AT 05:01They don’t cure. They don’t heal. But they let you breathe.

And sometimes… that’s enough.

Aaron Bales

January 9, 2026 AT 19:54Three things if you’re on opioids:

1. Keep a pill log. Write down every dose. You’ll be shocked how much you’re actually using.

2. Ask your doctor: ‘What’s my goal here?’ Not ‘Does it hurt less?’ - ‘Can I walk to the mailbox?’ ‘Can I hug my grandkid?’

3. If you haven’t tried CBT or PT - do it. Even for 4 weeks. You might be surprised.

And yes - naloxone. Get it. Keep it. Teach someone. It’s not about fear. It’s about responsibility.

You’re not weak for needing help. You’re weak if you refuse to get better.

Branden Temew

January 10, 2026 AT 07:35Here’s the uncomfortable truth: opioids don’t fix pain. They mask it. And masking is not healing.

But here’s the even more uncomfortable truth: some people don’t get to heal.

Some bodies are broken beyond repair. Some nerves scream forever. Some days, the only thing between you and screaming into the void is a pill.

So yes - taper. Yes - try alternatives. Yes - monitor. But don’t pretend that for some, the choice isn’t between pain and peace - it’s between agony and dignity.

And dignity? That’s not a statistic.

That’s a human right.