When a baby develops dry, itchy skin in the first few months of life, parents often worry about a rash. But that rash might be more than just a temporary irritation-it could be the first sign of a chain reaction called the atopic march. This isn’t just about eczema turning into asthma. It’s about how a broken skin barrier in infancy can set off a cascade of allergies, food sensitivities, and respiratory conditions later on. And here’s the key: you don’t have to wait for it to happen. What you do now-especially with skin care-can change the path.

What Exactly Is the Atopic March?

The atopic march describes how allergic diseases often show up one after another in children. It usually starts with eczema, sometimes as early as 2 to 6 months old. Then, over time, kids may develop food allergies, followed by allergic rhinitis (hay fever), and eventually asthma. For years, doctors thought this was a guaranteed sequence: eczema → food allergy → asthma. But recent studies show that’s not true for most kids. In fact, only about 3.1% of children with eczema follow that exact pattern. Most kids with eczema don’t go on to develop asthma. And many kids with asthma never had eczema. So why does this idea still matter? Because while the march isn’t inevitable, it’s real for a subset of children-and identifying them early can make a big difference. The real shift in thinking now is from a linear path to something called atopic multimorbidity. That means eczema, food allergies, and asthma often happen together or overlap, not strictly one after the other. The common thread? A weak skin barrier and an immune system that’s primed to overreact.Why Skin Barrier Breakdown Is the Starting Point

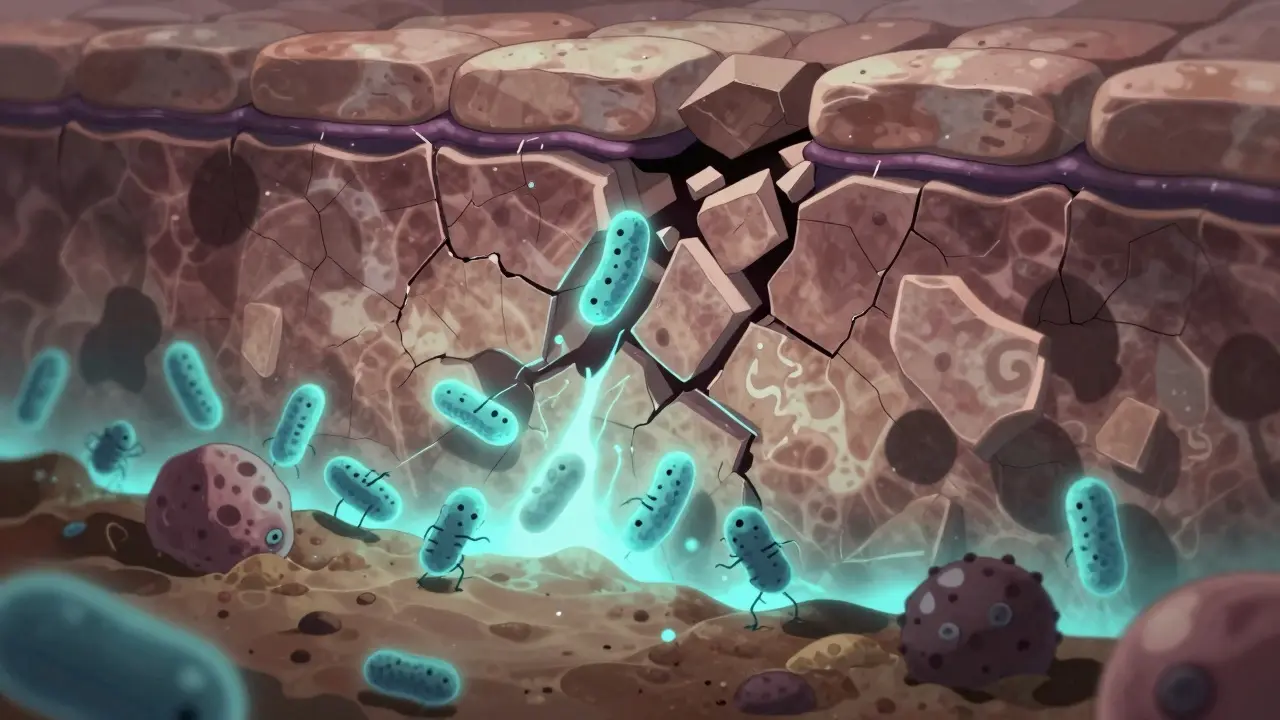

Your skin isn’t just a covering-it’s a shield. In babies with eczema, that shield is cracked. Tiny gaps let in dust, pollen, pet dander, and even food particles like peanut or egg that touch the skin. When these allergens slip through, the immune system sees them as invaders and starts making antibodies. That’s sensitization. But here’s the twist: if those same allergens get into the body through the mouth early on, the immune system learns to tolerate them. That’s why the LEAP study found that feeding peanut to high-risk infants with severe eczema reduced peanut allergy by 86%. Skin exposure = sensitization. Oral exposure = protection. The biggest genetic clue? Mutations in the filaggrin gene. This gene helps build the skin’s outer layer. Kids with filaggrin mutations are more likely to have severe eczema-and they’re also more likely to develop food allergies and asthma later. But here’s the catch: filaggrin mutations alone don’t cause allergies. They need the broken skin barrier to do damage. That’s why fixing the barrier early matters more than genetics. Other genes like TSLP and IL-33 also play roles. They’re like alarm buttons in the immune system, and when they’re too sensitive, the body overreacts to harmless things. These genes are shared across eczema, asthma, and allergic rhinitis, which is why these conditions often cluster in the same family.How Severe Eczema Changes the Risk

Not all eczema is the same. Mild flares on the cheeks? Lower risk. Deep, cracked, constantly itchy eczema that spreads to the arms and legs? That’s a red flag. Research shows kids with severe eczema are over 60% more likely to develop asthma than those with mild cases. And those with severe eczema are 3 to 4 times more likely to end up with multiple allergic conditions. The PreventADALL trial looked at babies with a family history of allergies and gave them daily emollients from birth. After a year, those babies had 20-30% less eczema. That’s huge. It suggests that keeping the skin moisturized from day one might stop the march before it starts. And it’s not just about creams. Babies born with dry skin-even before eczema shows up-are already at higher risk. That’s why dermatologists now say: if your baby’s skin feels rough or looks flaky, start moisturizing. Don’t wait for redness or itching.

What Skin Barrier Care Actually Looks Like

You don’t need fancy products. You need consistency.- Use fragrance-free, thick ointments like petroleum jelly or ceramide-rich creams. Lotions often have too much water and evaporate too fast.

- Apply twice a day-morning and night-even when the skin looks fine.

- Bath time should be short (5-10 minutes), lukewarm, and followed by patting dry, not rubbing.

- Apply moisturizer within 3 minutes after bathing, while the skin is still damp.

- Avoid harsh soaps. Use gentle cleansers only where needed, like the diaper area or armpits.

- Dress in soft, breathable fabrics like cotton. Wool and synthetic fibers can irritate.

The Gut-Skin Connection You Can’t Ignore

Your baby’s gut is just as important as their skin. Studies show that infants who develop allergies have different gut bacteria than those who don’t. Specifically, they’re missing microbes that produce butyrate-a compound that helps calm the immune system. Breastfeeding helps. So does avoiding unnecessary antibiotics in the first year. And while probiotics are still being studied, some evidence suggests certain strains (like Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG) may reduce eczema risk in high-risk babies. The bottom line: skin and gut are linked. What’s happening in the gut affects the skin, and vice versa. A healthy gut supports a balanced immune response. A damaged skin barrier lets allergens in, which can throw the gut off balance too.

When to Worry-and When to Relax

If your child has mild eczema and no family history of asthma or food allergies, the risk of a full atopic march is low. Don’t panic. Just keep the skin moisturized and avoid known irritants. But if your child has:- Severe, persistent eczema

- A parent or sibling with asthma or severe allergies

- Early-onset eczema (before 3 months)

- Cracked or bleeding skin

- Early peanut introduction (as early as 4-6 months, if cleared by a doctor)

- Testing for sensitization (but remember: sensitization doesn’t mean allergy)

- Monitoring for wheezing or breathing issues

What’s Next for Research

Scientists are now building tools to predict which babies are most likely to follow the atopic march. They’re combining genetic data, skin barrier tests, gut microbiome profiles, and early allergy testing to create risk scores. The goal? Not to scare parents, but to give them targeted advice: “Your child has a high risk-here’s exactly what to do.” The PreventADALL trial is still ongoing. Other studies are testing whether specific probiotics or dietary changes can alter immune development. One thing is clear: the future isn’t about treating allergies after they happen. It’s about stopping them before they start.Does every child with eczema develop allergies?

No. Only about 25% of children with eczema go on to develop asthma, and even fewer follow the full classic atopic march. Most kids with mild eczema don’t develop food allergies or allergic rhinitis. The key is identifying high-risk cases-those with severe eczema, family history, or early onset-so they can get targeted care.

Can moisturizing prevent food allergies?

Moisturizing alone won’t prevent food allergies, but it can reduce the risk when combined with early oral exposure. A broken skin barrier lets food proteins in through the skin, which can trigger sensitization. Keeping the skin intact with daily emollients lowers that risk. Meanwhile, feeding allergenic foods like peanut and egg early (under medical guidance) teaches the immune system to tolerate them. Together, these steps work.

What’s the difference between sensitization and allergy?

Sensitization means the immune system has made antibodies to a substance, like peanut or dust mites. But you might not have any symptoms. An allergy means those antibodies cause real reactions-hives, vomiting, wheezing, or anaphylaxis. About 80% of kids with eczema are sensitized to something, but only a fraction actually have clinical allergies. Testing can show sensitization, but only symptoms confirm an allergy.

Is there a cure for the atopic march?

There’s no cure yet, but there’s growing evidence you can stop or slow it. Early skin barrier repair, timely introduction of allergenic foods, and managing eczema aggressively can reduce the chance of developing asthma or multiple allergies. The goal isn’t to eliminate all risk-it’s to prevent the worst outcomes in the kids most likely to be affected.

Should I avoid allergenic foods if my baby has eczema?

No. Avoiding foods like peanut, egg, or milk can actually increase the risk of developing allergies. The LEAP study showed that early introduction of peanut in high-risk infants cut peanut allergy by 86%. Talk to your doctor about safely introducing these foods around 4-6 months, especially if your baby has severe eczema. Delaying exposure doesn’t help-it hurts.

Madhav Malhotra

January 12, 2026 AT 04:35So glad I found this! In India, we always use coconut oil for baby skin, but now I’m wondering if it’s enough. My cousin’s kid had eczema at 3 months and now has peanut allergy-scary stuff. Maybe we need to rethink what ‘natural’ means for skin care.

Alex Smith

January 13, 2026 AT 19:37Oh wow, so moisturizing is the new ‘don’t vaccinate your kid’? Because if I didn’t know better, I’d think this was a skincare influencer’s manifesto disguised as science. Next they’ll tell me to chant affirmations to my baby’s epidermis.

Roshan Joy

January 15, 2026 AT 05:14Really appreciate how this breaks down the science without fear-mongering. My niece had mild eczema and we started ceramide cream at 2 months-no food allergies at age 3. Small wins matter. 🌱

Adewumi Gbotemi

January 15, 2026 AT 22:27My son had dry skin since birth. We used Vaseline every day. No eczema, no allergies. Maybe it’s simple. Maybe we overthink.

Vincent Clarizio

January 17, 2026 AT 16:22Let’s be real-the atopic march isn’t a ‘march’ at all, it’s a capitalist conspiracy disguised as pediatric medicine. Big Pharma wants you to buy ceramide creams, probiotic gummies, and allergen introduction kits while ignoring the real root cause: our toxic, over-sanitized, Wi-Fi-blasted, glyphosate-sprayed world. The skin barrier? It’s not broken-it’s being assaulted by systemic neglect. We’ve replaced nature with nanotech lotions and called it progress. Wake up.

Jennifer Littler

January 18, 2026 AT 19:38From a clinical perspective, the filaggrin mutation data is compelling, but the effect size in real-world cohorts is often confounded by environmental co-factors like air pollution and microbiome diversity. The PreventADALL trial’s 20-30% reduction is statistically significant but not clinically transformative without adjunctive immunomodulatory strategies.

Sean Feng

January 19, 2026 AT 01:44Just put lotion on it. Done.

Priscilla Kraft

January 21, 2026 AT 00:35Love this so much! My daughter had severe eczema at 6 weeks-cracked hands, bleeding elbows. We started emollients twice daily and introduced peanut butter at 5 months (with pediatrician approval). She’s 2 now and has zero allergies. This isn’t magic, it’s medicine. 🙌

Christian Basel

January 22, 2026 AT 21:28Studies show X, but correlation ≠ causation. Also, why is everyone assuming eczema is always the first domino? What if it’s just a symptom, not the trigger? The gut-brain-skin axis is still theoretical. We’re putting the cart before the horse.

Michael Patterson

January 24, 2026 AT 19:03People need to stop being so paranoid. My kid had eczema, I didn’t do any of this fancy stuff, now he’s 10 and plays soccer. You think moisturizing prevents asthma? Bro, my grandpa smoked 3 packs a day and lived to 92. Nature’s got a plan. Stop overengineering baby skin.

Matthew Miller

January 25, 2026 AT 12:03This post is pure wellness cult propaganda. You’re telling parents to spend hundreds on ‘ceramide-rich’ creams while ignoring that 90% of kids with eczema never develop asthma? That’s not prevention, that’s fear-based monetization. Get real.

Priya Patel

January 27, 2026 AT 09:08My mom used Vaseline on me when I was a baby and I turned out fine 😅 but now I’m reading this and I’m like… maybe she was a genius? I’m starting on my nephew tomorrow. No stress, just vibes and lotion. 🌿

Jason Shriner

January 28, 2026 AT 19:46So… you’re saying if I slather my baby in petroleum jelly, I can skip the whole ‘parenting’ thing? Genius. Next you’ll tell me to just ignore the screaming and apply more cream. 🤡