Not all dementia is the same

When someone says "dementia," most people picture memory loss-forgetting names, repeating questions, getting lost in familiar places. But that’s only part of the story. Vascular dementia, frontotemporal dementia (FTD), and Lewy body dementia (LBD) are three very different conditions that all fall under the dementia umbrella. They affect different parts of the brain, show up in different ways, and need completely different care. Getting the right diagnosis isn’t just about labeling-it changes everything from treatment to safety to how families plan for the future.

Vascular dementia: The silent damage from blocked blood flow

Vascular dementia happens when blood flow to the brain is interrupted. It’s not caused by dying brain cells from protein buildup, like in Alzheimer’s. It’s caused by strokes, mini-strokes (TIAs), or long-term damage from high blood pressure, diabetes, or clogged arteries. Every time a blood vessel gets blocked or bursts, a small area of brain tissue dies. Over time, these tiny injuries add up.

Unlike Alzheimer’s, where memory fades slowly, vascular dementia often shows up in steps. A person might seem fine one month, then suddenly struggle to follow a conversation or forget how to pay bills after a stroke. Then they stabilize for a while-only to decline again after another vascular event. This pattern is a major red flag.

Symptoms go beyond memory. People with vascular dementia often have trouble with planning, organizing, and making decisions. They might walk unsteadily, lose bladder control, or feel emotionally flat. Hallucinations and delusions can happen too, especially if the damage is in the frontal lobes. The biggest risk? Another stroke. That’s why managing blood pressure (under 130/80 mmHg), cholesterol, and blood sugar isn’t just helpful-it’s essential. Medications like aspirin or statins can slow progression, but only if started early.

Frontotemporal dementia: When personality changes before memory does

FTD is the dementia that catches families off guard because it hits younger people-often in their 50s or 60s-and the first signs look nothing like Alzheimer’s. Instead of forgetting where they put their keys, someone with FTD might start acting completely out of character. They might make inappropriate comments, spend money recklessly, lose all interest in family, or eat compulsively. Some become emotionally numb. Others cry or laugh at the wrong times.

This isn’t a psychiatric issue. It’s brain shrinkage. FTD targets the frontal and temporal lobes-the parts that control behavior, judgment, language, and social rules. Brain scans show clear atrophy in these areas. Memory stays strong for a long time, which is why it’s often mistaken for depression, bipolar disorder, or even midlife crisis. Up to half of FTD cases are misdiagnosed at first.

There are three main types. Behavioral variant FTD causes personality shifts. Primary progressive aphasia affects speech-some people struggle to find words, others speak fluently but say nonsense. A third group develops movement problems like muscle stiffness or tremors, similar to Parkinson’s. There’s no cure. Medications like SSRIs can help with impulsivity or mood swings, but they don’t stop the disease. Speech therapy helps with language loss. The hardest part? Families often don’t recognize the changes as illness-they think their loved one is being selfish or lazy. Education is the first step to better care.

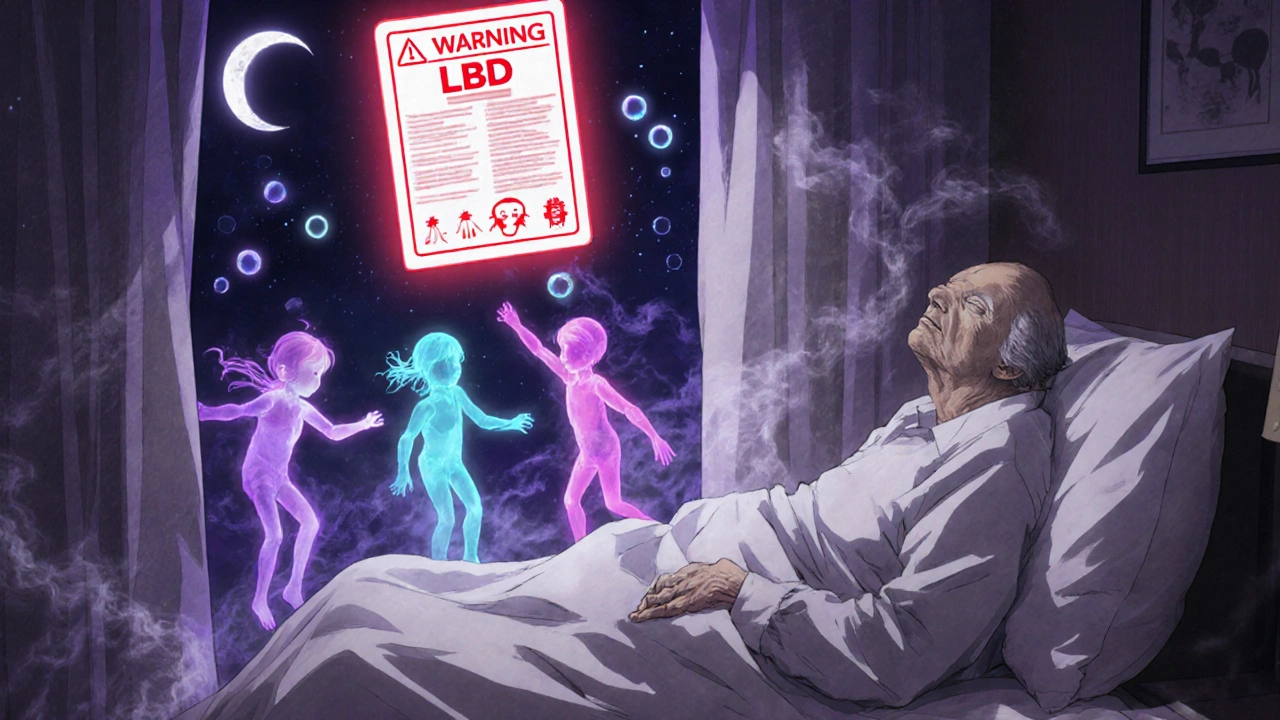

Lewy body dementia: The tricky mix of brain fog, hallucinations, and movement issues

Lewy body dementia is one of the most misunderstood types. It’s not one disease-it’s two. Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD) are the same condition, just diagnosed differently based on timing. If dementia comes first-or within a year of movement problems-it’s DLB. If Parkinson’s symptoms come first and dementia follows after a year or more, it’s PDD.

What makes LBD so dangerous? Three core signs: fluctuating attention, visual hallucinations, and Parkinson-like movement issues. A person might be alert and talking clearly one minute, then zone out, stare blankly, and not respond the next. They might see people or animals that aren’t there-often detailed and vivid, like a child playing in the corner. These hallucinations aren’t always scary to the person; they might just comment on them calmly.

They also have movement problems: stiff muscles, slow steps, shuffling gait, reduced facial expression. Many have REM sleep behavior disorder-acting out dreams, kicking, yelling in their sleep. And here’s the critical warning: standard antipsychotic drugs used for hallucinations in Alzheimer’s can be deadly in LBD. Up to 75% of people with LBD have severe, even fatal reactions to these medications. Even mild ones like haloperidol can cause sudden stiffness, fever, or cardiac arrest.

Doctors use cholinesterase inhibitors like rivastigmine to help with thinking and hallucinations. Sleep and movement symptoms are managed with other targeted drugs. Diagnosis relies on specific criteria: at least two core symptoms plus supporting evidence from brain scans like DaTscan. Misdiagnosis is common-up to 75% of LBD cases are initially called Alzheimer’s. That’s why getting the right diagnosis can reduce hospital stays by 30%.

Why the differences matter more than you think

These three types aren’t just different in symptoms-they need different treatments, different safety plans, and different caregiver strategies. Giving someone with LBD an antipsychotic meant for Alzheimer’s can kill them. Prescribing a memory drug like donepezil to someone with vascular dementia might do nothing if their blood pressure isn’t controlled. Treating FTD like depression with antidepressants alone misses the neurological root.

Diagnosis requires more than a memory test. Vascular dementia needs MRI scans to spot strokes or white matter damage. FTD requires brain imaging showing frontal/temporal shrinkage and neuropsychological testing focused on behavior and language-not memory. LBD needs evaluation of cognitive fluctuations, hallucinations, and movement, often confirmed with DaTscan.

And the stakes are high. The Alzheimer’s Association estimates that up to 40% of people with Alzheimer’s also have Lewy bodies, making diagnosis even harder. Many patients are caught in the middle-showing mixed symptoms. That’s why specialists in memory disorders are critical. General neurologists might miss the subtleties. A dementia clinic with experience in all three types gives the best shot at accurate diagnosis.

What you can do now

If you or someone you know is showing signs of dementia, don’t wait. Early detection makes a difference. Track changes: Is memory fading slowly, or did behavior change suddenly? Are hallucinations happening? Is movement getting stiff? Write it down. Bring it to a doctor who specializes in dementia-not just a primary care provider.

Ask for brain imaging. Ask about blood pressure and diabetes control. Ask if the symptoms fit vascular, frontotemporal, or Lewy body patterns. Don’t accept a vague "it’s probably Alzheimer’s" answer. Push for clarity. The right diagnosis means better medication choices, fewer dangerous side effects, and more realistic planning.

For caregivers: Learn the signs of each type. LBD hallucinations aren’t always delusions-they’re part of the disease. FTD personality changes aren’t defiance-they’re brain damage. Vascular dementia isn’t just aging-it’s a warning sign of heart and blood vessel problems. Knowledge isn’t just helpful. It’s protective.

What’s on the horizon

Research is moving fast. Blood tests are being developed to detect early signs of vascular injury or abnormal proteins. For LBD, drugs targeting alpha-synuclein (the protein forming Lewy bodies) are in clinical trials. For FTD, gene therapies are being tested in people with inherited forms. And the SPRINT-MIND trial proved that lowering blood pressure to under 120 mmHg reduces the risk of mild cognitive decline by 19%-a powerful reminder that what’s good for the heart is good for the brain.

But funding still lags. Alzheimer’s gets billions in research dollars. LBD and FTD together get less than $50 million annually-despite affecting millions. That’s changing slowly, but awareness is the first step. Talk about it. Ask questions. Demand better diagnostics. Because when it comes to dementia, not all types are created equal-and understanding the difference saves lives.

Sam txf

November 28, 2025 AT 08:37This post is a goddamn masterpiece. Most people think dementia is just old folks forgetting where they put their damn keys, but nah - it’s a fucking orchestra of brain rot, and nobody’s listening. Vascular dementia? That’s your blood pressure screaming for help. FTD? Your uncle’s ‘midlife crisis’ is his frontal lobe dissolving. And LBD? Don’t even get me started on how hospitals poison people with antipsychotics like they’re treating a bad trip. This isn’t aging - it’s a systemic failure.

Brandon Trevino

November 29, 2025 AT 18:42While the article provides a clinically accurate overview of three distinct neurodegenerative syndromes, it lacks quantitative epidemiological context. The CDC reports vascular dementia accounts for approximately 10-20% of all dementia cases in the U.S. with a mean age of onset at 67.3 years. FTD exhibits a bimodal distribution peaking at 58 and 65. LBD prevalence is underdiagnosed by 68% according to the Lewy Body Dementia Association 2023 white paper. Diagnostic criteria must be standardized under DSM-5-TR and ICD-11 frameworks to reduce misclassification bias.

Denise Wiley

November 30, 2025 AT 18:44I just want to say thank you for writing this. My mom had LBD and we went through hell because the first doctor called it Alzheimer’s and gave her meds that made her worse. She started hallucinating more, couldn’t walk, and we almost lost her. It took six months and three specialists to get it right. I wish I’d had this article back then. You’re helping so many families. Please keep sharing this kind of stuff - it’s life-saving.

Austin Simko

December 2, 2025 AT 03:02Big Pharma pushed these labels to sell drugs. The real cause is glyphosate in your food and 5G brain frying. They don’t want you to know.

Nicola Mari

December 3, 2025 AT 04:35It’s appalling how little society invests in dementia research compared to cancer. People with dementia are often treated as burdens rather than human beings. Families are left to navigate this alone while the system watches. This isn’t medical neglect - it’s moral decay. And yet, no one talks about it unless it happens to their own family. Shameful.

George Hook

December 3, 2025 AT 19:11I’ve been a caregiver for my father with vascular dementia for six years now. He had three mini-strokes over 18 months. The stepwise decline was brutal - one day he could balance his checkbook, the next he couldn’t tell me what month it was. We didn’t know it was vascular until his neurologist pointed out the white matter lesions on the MRI. The biggest lesson? Blood pressure control isn’t optional. It’s the difference between a slow fade and a rapid spiral. I wish more people understood that managing hypertension isn’t just about avoiding heart attacks - it’s about keeping someone’s mind intact.

jaya sreeraagam

December 5, 2025 AT 06:34As someone from India where dementia is still stigmatized as 'being crazy' or 'possession', this article is a gift. My aunt had FTD and we thought she was just being rude - she’d scream at the TV, spend all her savings on useless things, and forget her own children’s names. No one wanted to take her to a doctor because ‘it’s just old age’. We finally got her diagnosed after a neighbor who worked in a US hospital shared this exact info. Now she’s on sertraline and speech therapy. It’s not a cure, but it’s dignity. Please translate this into Hindi, Tamil, Bengali - it will save lives in our communities too.

Katrina Sofiya

December 6, 2025 AT 19:27This is one of the most thoughtful, well-researched pieces I’ve read on dementia in years. Thank you for breaking down the differences with such clarity. I especially appreciate the emphasis on why misdiagnosis is dangerous - it’s not just academic, it’s lethal. I’ve seen families waste years chasing the wrong treatment because no one explained the nuances. You’ve given them a roadmap. Keep doing this work. The world needs more of this kind of compassion and precision.

kaushik dutta

December 7, 2025 AT 08:10From a neurology perspective in South Asia, the cultural misinterpretation of FTD is catastrophic. Behavioral disinhibition is labeled as 'lack of upbringing' or 'Western influence'. Families shame the patient instead of seeking care. And LBD? In rural clinics, they prescribe antipsychotics like candy. The DaTscan isn’t even available in 90% of hospitals here. We need grassroots education, not just Western-style white papers. We’re training community health workers to recognize fluctuating cognition and REM behavior disorder - it’s working. But funding? Zero. This is a global crisis masked by stigma and silence.

doug schlenker

December 9, 2025 AT 04:16I read this while sitting in my dad’s hospice room. He had mixed dementia - Alzheimer’s and Lewy bodies. The hallucinations were quiet - he’d just smile at the corner and say, ‘There’s the little girl again.’ We didn’t know it was part of the disease until we found this article. No one told us antipsychotics could kill him. I’m so glad someone finally wrote this. Not for the doctors. For the people like me, holding their parent’s hand, terrified and alone.

Olivia Gracelynn Starsmith

December 9, 2025 AT 13:54Important information. Early detection saves lives. Track changes. Get imaging. Ask questions. Don’t accept vague answers. Knowledge is protection. This is critical for families navigating this journey. Thank you for sharing.

Skye Hamilton

December 10, 2025 AT 12:09Actually… I think this is all just a distraction. The real issue is that people are living too long. We’ve medicalized normal aging. Dementia isn’t a disease - it’s a societal failure to accept mortality. Why spend millions on scans and drugs when we could just teach people to die with dignity? Also, I think the whole Alzheimer’s industry is a scam. I’ve read blogs that say it’s all about profit.

Maria Romina Aguilar

December 11, 2025 AT 15:08While I appreciate the effort, I must point out - the article assumes a Western medical paradigm, which is inherently colonial. In many Indigenous cultures, cognitive changes are understood through spiritual frameworks, not neuroimaging. The insistence on MRI, DaTscan, and DSM criteria erases alternative epistemologies. Also - why is the tone so clinical? Where is the humanity? Where are the voices of those living with dementia? You speak for them, but not with them.

Hannah Magera

December 12, 2025 AT 00:36This helped me understand why my grandma kept repeating the same story every hour. I thought she was just being stubborn. Turns out her brain couldn’t form new memories. I didn’t know vascular dementia could look like that. I’m going to talk to my doctor about checking my blood pressure now. Thanks for explaining it so simply.

Evelyn Shaller-Auslander

December 13, 2025 AT 10:23My sister has FTD. She’s 56. Last week she tried to pay a parking ticket with Monopoly money. I didn’t laugh - I cried. But reading this? It didn’t fix anything. But it made me feel less alone. Thank you.

Sam txf

December 13, 2025 AT 14:46Replying to @5130 - yeah, sure, let’s just let people rot because you think aging is ‘a societal failure’. You’re not helping. You’re just being a dick. And @5131 - yes, cultural context matters, but telling a family their loved one is ‘possessed’ instead of getting them a scan? That’s not dignity, that’s death by ignorance. We need both - science and compassion. Not either/or.