What Are Colorectal Polyps?

Colorectal polyps are small growths that stick out from the inner lining of your colon or rectum. They’re common - about 30 to 50% of adults over 50 will have at least one. Most don’t cause symptoms, and many are found during routine colonoscopies. But not all polyps are the same. Two major types - adenomas and serrated lesions - are known to turn into cancer over time. Knowing the difference matters because how they grow, how hard they are to spot, and how quickly they turn dangerous vary a lot.

Adenomas: The Classic Precancerous Polyp

Adenomas make up about 70% of all precancerous polyps. They’re the type doctors have been watching for decades. Under the microscope, they look like disorganized glandular tissue. There are three main subtypes, and size and shape tell you how risky they are.

- Tubular adenomas are the most common - about 70% of all adenomas. They’re usually small, round, and grow like little tubes. If they’re under half an inch (1.27 cm), the chance of cancer inside is less than 1%.

- Tubulovillous adenomas mix tube-like and finger-like growths. These make up about 15% of adenomas and carry a higher risk. When they’re bigger than 1 cm, about 10-15% may already have cancer cells.

- Villous adenomas are the rarest - only 15% of adenomas - but the most dangerous. They’re flat, spread out, and hard to remove completely. Their cancer risk jumps to 15-40% if they’re over 2 cm.

Size is critical. A polyp under 1 cm has a very low chance of cancer. One over 1 cm? That’s when you start worrying. Villous features - even if just a small part of the polyp - raise the risk by 25-30% compared to pure tubular ones. That’s why doctors don’t just remove them - they send them to the lab to check for these details.

Serrated Lesions: The Stealthy Pathway to Cancer

Serrated lesions are trickier. They account for 20-30% of all colorectal cancers, yet they’re less common than adenomas. The name comes from their "sawtooth" edge under the microscope - like tiny teeth along the crypts. There are three kinds, but only two really matter for cancer risk.

- Hyperplastic polyps are usually harmless, especially if they’re small and in the lower colon. They rarely turn cancerous.

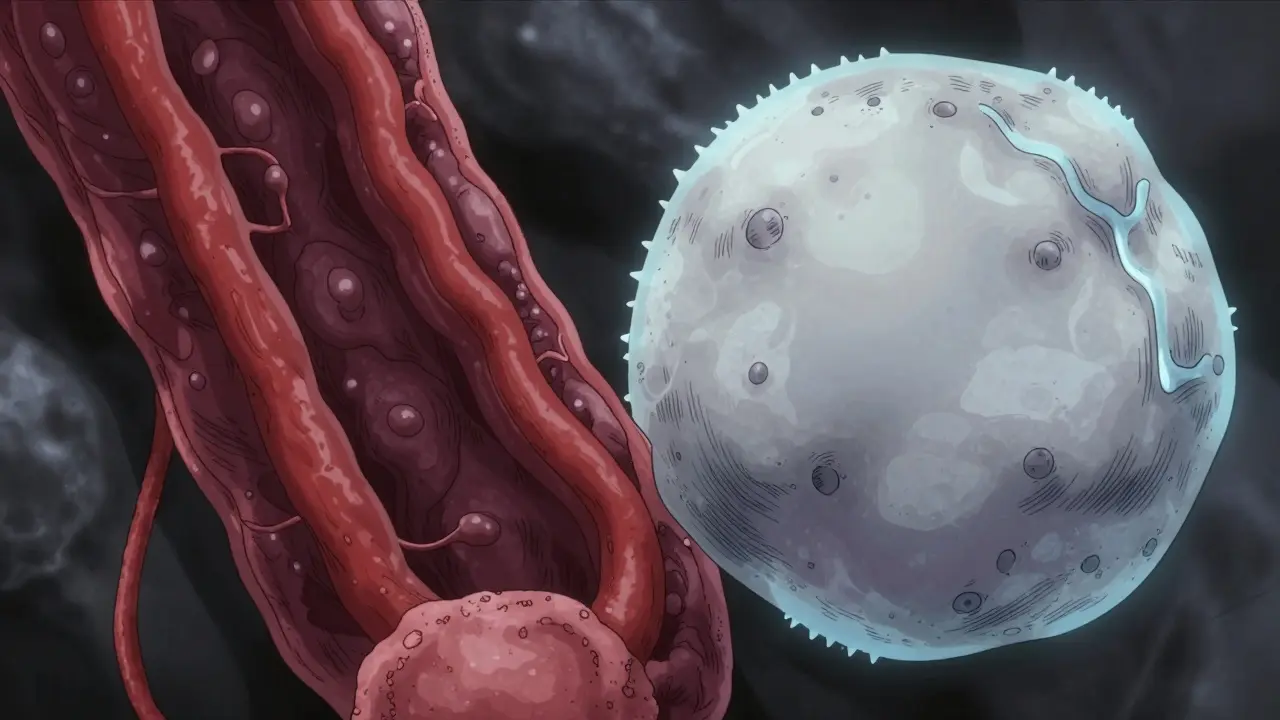

- Sessile serrated adenomas/polyps (SSA/Ps) are the big concern. They’re flat, often hidden in the right side of the colon (cecum or ascending colon), and grow slowly but steadily. About 13% of SSA/Ps already show high-grade dysplasia or early cancer when removed. They’re hard to see during colonoscopy because they’re flat, pale, and blend into the colon wall.

- Traditional serrated adenomas (TSAs) are rarer but aggressive. They often have a mushroom-like shape and can turn cancerous faster than SSA/Ps.

SSA/Ps are especially dangerous because they hide. They don’t bulge out like a mushroom - they sit flat, sometimes with a slight bump. Under magnifying colonoscopy, they show round, open pits and tangled blood vessels. Because they’re often in the proximal colon, they’re missed more often than adenomas. Studies show a 2-6% miss rate during standard colonoscopy - meaning one in 20 of these could be overlooked.

How Detection Differs Between the Two

Not all polyps are easy to find. Pedunculated polyps - those with a stalk - are like little mushrooms on a stem. Easy to spot and remove. Sessile and flat polyps? Not so much.

Adenomas often stick out clearly. Even villous ones, though flat, tend to be redder and more textured. SSA/Ps are pale, sometimes covered in mucus, and blend in. That’s why AI-assisted colonoscopy systems - like GI Genius - are becoming standard. In trials, they boosted adenoma detection by 14-18%. For SSA/Ps, the improvement is even more critical. A missed SSA/P can mean cancer five to ten years later.

Location matters too. Adenomas are common in the lower colon and rectum. SSA/Ps? Up to 70% are found in the right side - the cecum and ascending colon. That’s harder to clean well before a colonoscopy, and the scope’s view is less clear there. Many patients with right-sided SSA/Ps have no symptoms at all. When symptoms do appear, they’re vague: blood in stool, unexplained anemia, or changes in bowel habits.

What Happens After Removal?

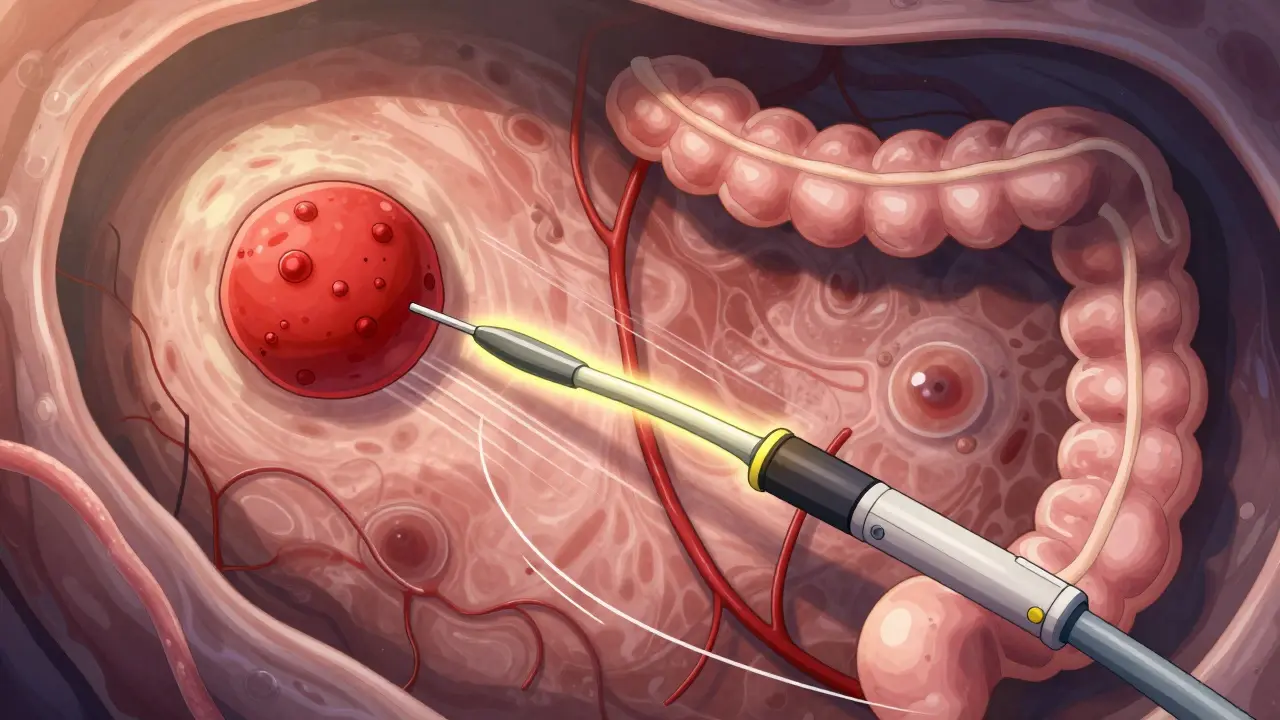

Removing a polyp during colonoscopy is the standard treatment. Success rates are high - 95-98% for adenomas under 2 cm. But for larger SSA/Ps (>2 cm), removal success drops to 80-85%. Why? Because they’re flat. If even a tiny bit is left behind, it can regrow.

After removal, the lab checks for cancer cells, depth of invasion, and margins. If cancer is found, you might need surgery. But if it’s just a precancerous polyp, your next step is surveillance. How often you get screened again depends on what you had.

For adenomas under 1 cm with low-grade dysplasia: repeat colonoscopy in 7-10 years.

For SSA/Ps ≥10 mm: most U.S. guidelines say 3 years. But in Europe, some recommend 5 years. Why the difference? European studies show slower progression. But since SSA/Ps can turn cancerous without warning, most U.S. doctors err on the side of caution.

And here’s the key: having any precancerous polyp - adenoma or serrated - raises your lifetime risk of colon cancer by 1.5 to 2.5 times. But that doesn’t mean you’ll get cancer. Most people never do. The goal isn’t fear - it’s vigilance.

Why Molecular Pathways Matter

It’s not just about what a polyp looks like. It’s about what’s happening inside.

Adenomas usually follow the "chromosomal instability" pathway. That means mutations in genes like APC kick off the process. Think of it like a broken brake pedal - cells keep dividing.

Serrated lesions follow the "CpG island methylator phenotype" (CIMP) pathway. This is about gene silencing - turning off tumor suppressor genes with chemical tags. BRAF mutations are common here. These polyps don’t grow fast, but they quietly turn cancerous through epigenetic changes.

This is why future screening is moving toward molecular testing. Soon, doctors may analyze a polyp’s DNA right after removal to predict if it’s likely to come back or turn cancerous. That could mean fewer unnecessary colonoscopies. Right now, over 6.5 million surveillance colonoscopies are done in the U.S. each year. Experts think personalized follow-up based on molecular markers could cut that by 20-30%.

What You Can Do

If you’ve had a polyp removed, stick to your follow-up schedule. Don’t skip it. Even if you feel fine. Most cancers develop silently.

If you haven’t been screened yet - get screened. Starting at age 45 (or earlier if you have family history) is now standard. Colonoscopy is still the gold standard because it finds and removes polyps in one go.

Don’t rely on stool tests alone if you’ve had a serrated polyp. They’re good for initial screening, but they can miss flat lesions. Colonoscopy is the only way to be sure.

And yes - lifestyle helps. Eat more fiber, limit red and processed meats, stay active, don’t smoke, and keep your weight in check. These won’t erase your risk if you’ve had a polyp, but they lower your overall chance of cancer.

Final Thought

Adenomas and serrated lesions are different, but both are preventable. The key is finding them early and removing them completely. It’s not about being scared of polyps. It’s about knowing they’re there, understanding what they mean, and taking action. Most people who have them never get cancer - because they got screened. That’s the real win.

Henriette Barrows

December 28, 2025 AT 17:58I had my first colonoscopy last year and found out I had a tiny tubular adenoma. Honestly, I was terrified-but then my doctor explained it like a benign pimple that just needed popping. Now I feel like a superhero who beat cancer before it even started. Thanks for breaking this down so clearly.

Alex Ronald

December 30, 2025 AT 07:59Adenomas are the classic villains, but SSA/Ps are the silent assassins. I’ve seen too many cases where a flat lesion was missed because the prep wasn’t perfect or the doc rushed. AI-assisted colonoscopy isn’t futuristic-it’s necessary now. If your hospital doesn’t use GI Genius, ask why.

Teresa Rodriguez leon

January 1, 2026 AT 02:41Ugh. I hate colonoscopies. The prep is worse than the procedure. Why can’t we just have a blood test or something? This whole thing feels like punishment.

Aliza Efraimov

January 2, 2026 AT 07:23Let me tell you something that kept me up at night after my diagnosis: I had a 1.8cm sessile serrated polyp removed from my ascending colon. The doc said it was borderline cancer already. I didn’t know these things could hide like ninjas. I thought polyps were just little bumps you could see. Turns out, they’re sneaky little bastards that blend into the wall like camouflage. I’m now on a 3-year surveillance schedule and I don’t even drink soda anymore. If you’re over 45 and haven’t been screened, stop reading this and book your damn appointment. Your future self will thank you.

Nisha Marwaha

January 3, 2026 AT 10:39The molecular pathways are critical for risk stratification. Adenomas follow the CIN pathway driven by APC mutations, whereas serrated lesions exhibit CIMP with BRAF V600E hypermethylation leading to MLH1 silencing. This dichotomy informs not only surveillance intervals but also emerging liquid biopsy applications. Future screening algorithms will likely integrate epigenetic signatures for dynamic risk profiling.

Amy Cannon

January 4, 2026 AT 11:46So, like, I read all this and I’m like… wow. Colon polyps? I didn’t even know they had names. I thought they were just… lumps. But now I get it-adenomas are like the old-school bad guys, and the serrated ones are the secret agents. And the right side? That’s like the dark alley where no one looks. I’m gonna go get screened next week. I promise. Even if the prep is gross. I’m not scared anymore. I’m just… ready.

Himanshu Singh

January 5, 2026 AT 07:19Great post! I got my first polyp at 42-tubular, under 1cm. My doc said it was fine, but I’ve been extra careful since. I eat more veggies, cut out bacon, and walk every day. Still, I’m scared to go back for my next scope. Any advice? I’m from India and we don’t talk about this stuff much.

Jasmine Yule

January 6, 2026 AT 08:01Just had a 1.5cm SSA/P removed last month. The doc said it had high-grade dysplasia. I cried in the recovery room. But then I read this and realized-this isn’t a death sentence. It’s a wake-up call. I’m going to start a support group for people who’ve had serrated polyps. We need to talk about this. No more silence. 💪

Jim Rice

January 8, 2026 AT 05:11Actually, most of this is exaggerated. Adenomas aren’t that dangerous, and SSA/Ps are overhyped. I’ve seen patients get 3 colonoscopies in 5 years for tiny polyps. The system is broken. You’re being scared into unnecessary procedures. Just eat less meat and call it a day.

Manan Pandya

January 8, 2026 AT 09:26Excellent breakdown. For those wondering about surveillance intervals: the 3-year recommendation for SSA/P ≥10mm is based on the 2020 US Multi-Society Task Force guidelines, which prioritize early detection due to the unpredictable progression of CIMP-high lesions. However, in low-resource settings, a 5-year interval remains acceptable if high-quality colonoscopy is not consistently available.

Paige Shipe

January 9, 2026 AT 08:12This article is dangerously misleading. You say adenomas are "the classic precancerous polyp"-but what about the 30% of cancers that come from serrated lesions? You’re reinforcing outdated paradigms. The medical community still clings to adenoma-centric models, and that’s why so many patients get missed. This isn’t science-it’s dogma.

Tamar Dunlop

January 9, 2026 AT 17:35It is truly remarkable how the anatomical distribution of serrated lesions-predominantly in the proximal colon-correlates with the challenges of bowel preparation and endoscopic visualization. One must also consider the interplay between microbiome composition and mucosal inflammation in the right-sided colon, which may facilitate the epigenetic silencing observed in CIMP-positive lesions. This is not merely a matter of detection-it is a systemic biological phenomenon.

David Chase

January 11, 2026 AT 15:57AMERICA IS THE ONLY COUNTRY THAT DOES THIS RIGHT!! 🇺🇸 Everyone else is sleeping on colon cancer! We have AI, we have guidelines, we have awareness. Meanwhile, India? Canada? They’re still using stone-age methods. My cousin got diagnosed because he ignored symptoms for 3 years. He’s fine now, but he’s lucky. We need to export our system to the world. #ColonCancerAwareness #USAWins

🚨🩸🩺Emma Duquemin

January 13, 2026 AT 14:39My polyp story is wild-I had a villous adenoma the size of a grape, and my doc said, "This thing looks like a coral reef in there." I was like, "Cool, but why am I still alive?" Turns out, I’ve been eating kale smoothies since college and walking 10K steps daily. My body was fighting. Don’t panic. Just show up. Get screened. Eat your greens. Move your butt. And if you’re scared? Cry, scream, then book the appointment. You got this.

Kevin Lopez

January 14, 2026 AT 10:08Adenoma = bad. Serrated = worse. Surveillance = mandatory. Done.